Above photo is our 2018-19 Volunteer Team

Spring Fundraising:

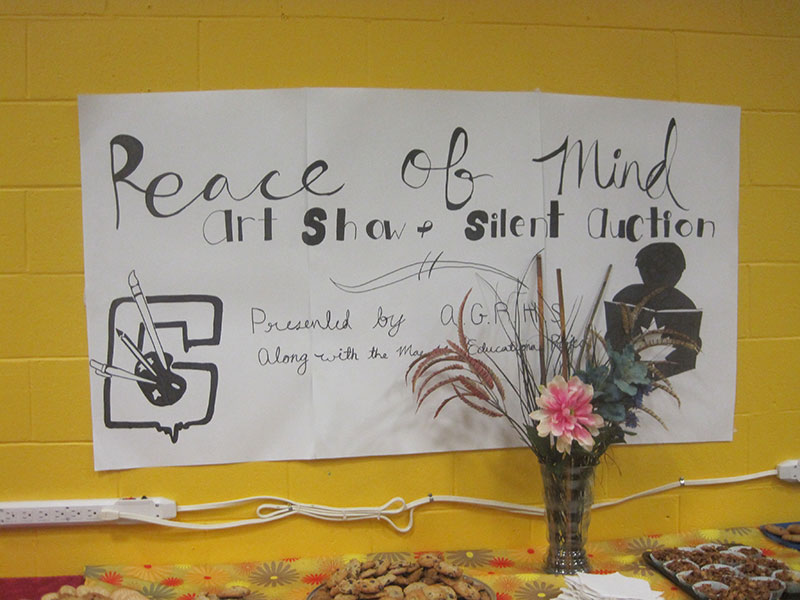

Our raffle and our Thai-Burmese benefit supper and a special thanks from MSEP to the Galt Art Concentration Students for auctioning their artwork to support kids in Mae Sot.

Galt Art Concentration Students talk about their art and their desire to use it to support Burmese youth in migrant schools. With a little help from some dynamic teachers (such as Sigal Hirshfeld seen in the photo talking with a parent), their art auction, which took place on the evening of March 23rd, netted $1300!

Annual Gourmet Thai-Burmese Benefit Supper

The Mae Sot Education Project invites you to attend its annual Gourmet Thai-Burmese Benefit Supper. With music, raffle draw &

talks by volunteers.

Saturday, April 28th, 6:30 p.m.

Oasis Christian Centre

219 Queen Street, Lennoxville

Tickets $50

Contact project committee members for tickets. A tax receipt for charitable donation will be given for $30. If you are unable to attend but would like to support our project, donations are always welcome!

Volunteer Experiences – in Mae Sot and Beyond

The Volunteer’s Major Challenge: Communication!

By Dania Paradis-Bouffard, 2017 Volunteer, writing from Mae Sot in March 2018

Dania with school head, Naw Tha Zin

What does it mean to communicate – I mean really communicate – across cultures? I have been volunteering as an English teacher in two Burmese migrant schools along the Myanmar-Thai border through the Mae Sot Education Project for nine months now. Usually, MSEP volunteers stay in Mae Sot from June to December. I extended my stay in Mae Sot for three more months to work for and become more deeply involved with the migrant community. I was warned early on that I would fall in love with the Myanmar migrants and their culture, and as predicted, I did – even before I could realise what was happening. Thus, this self-reflection is written with love and appreciation for both the Mae Sot Education Project and the Myanmar migrant community in Mae Sot.

As a new, inexperienced English teacher, the challenges I faced were numerous. They ranged from how to grab my students’ attention successfully to remembering their exotic names. For the most part, these two difficulties faded away with time. However, much to my dismay, others stuck to me like my milky, untanned skin. Miscommunication was the everlasting and strongest enemy that I faced in Mae Sot.

Dania with school head, Naw Tha Zin

Miscommunications between us visitors and the members of the migrant schools took different forms. Partly because of their lack of resources and effective organisational tools, the schools can appear chaotic. For example, on multiple occasions, I have walked into an empty school without any idea of where either teachers or students were. When it first happened, I told myself that I was a new teacher and that the staff members were not used to having the extra responsibility of telling me about the holiday schedule. As time went by and I started taking the time to ask for details about the school’s closing days, I still did not always have the right information.

Later on, I learned that some of my fellow MSEP volunteer teachers also experienced this problem. Most migrant schools tend not to keep volunteers in the loop. I began to realise that this exclusion was not personal by any means. It was apparently common for foreigners, who are considered outside the regular staff team, to be left out of the day-to-day staff communications.

A lack of communication in the context of the school schedule is one thing, but when a project needing both time and organisation arises, small miscommunications take on bigger proportions. As I tried to help one of the schools I was volunteering for, I missed out on crucial information. I entered the school’s community feeling very excited and creative but also very naive. I had many ideas and wanted to take initiatives in order to help this school to the best of my capacities. However, I eventually hit a wall realising that the wishes of the school’s management team were not aligned with the projects that I was devising. Why would I even attempt to work on something without the agreement of the school? I am a volunteer after all. I am here to offer my help but would never under any circumstance want to pressure the staff members of the school to embark on a project that they do not believe in. The answer is simple: I was never informed of their reluctance, their different priorities.

For example, I had the idea to create an online budget sheet template that would do calculations automatically and economise precious time for my overworked headmistress. The first few times I mentioned this idea, she reacted positively to my initiative. I would have even described her expression as excited. Later on when I became more serious about creating the budget template, and I started asking her questions on the data I needed to create the sheet, she slowly started to withdraw. She was not excited anymore but was still smiling at my enthusiasm, seemingly positive about the project. Gradually, I started to notice how she avoided giving out details and slowly realised that she did not want to invest time in it. It took me quite a while to pick up on her subtle hints. I had built up my hopes on nothing but my own desire to be useful and my Canadian ideas about what that would entail. She never overtly told me that she did not want or could not make this project flourish. I had to figure it out.

I have come to a few conclusions about the problem of poor communication. First, our Burmese partners are naturally very warm, welcoming and trusting, but they are also used to foreigners, foundations and organisations trying to take control of their schools and reorganise their systems in ways that make more sense – to them only. Our partners are afraid of losing their grip on what is rightfully theirs and have good reasons for their management styles. Thus while the headmistress of my school unequivocally welcomed me, a foreign volunteer, with open arms, she also kept my project proposals that could alter the system she had put in place at bay.

Second of all, as lovely people from a culture that discourages confrontation, our partners avoid entering into conflicts at all costs. Overt assertiveness is rare. It does not help that as a volunteer, I am associated with MSEP’s financial donations to the schools. One can understand how this headmistress would not want to reject openly the projects of MSEP’s representative. Its funding, however small, helps the school to remain open. Therefore, in the school team’s eyes, good relations need to be preserved at all cost. From my perspective, an explanation of their true needs and wants would have gone a long way to making me a more effective volunteer.

Before I even set foot in Mae Sot, I was warned that communication with the school team would not be easy and that I would have to make sure that any project that I sought to implement was wanted. Being now at the end of my tenure and in a position to give a bit of advice on volunteer work abroad, I would add to this first statement that ‘making sure the project is wanted’ might not be easy in every community. The true expression of the community’s thoughts and needs might be a rare jewel that the volunteer needs to dig out carefully in order to appreciate and serve it effectively.

Dania playing a game with her students

The Word of the Day is ‘Detention’

By Katharine McKenney, 2017 Volunteer

A note: Katharine’s story shows how some volunteers are motivated by their experience with MSEP to seek other similar experiences. In addition, it shows that the project makes them good candidates for these posts!

Kat with her new students

What does one do after the intense experience of volunteering with MSEP? Wanting more of this experience of working with forceably displaced people, since leaving Mae Sot in December, I have found a second “home” on the island of Lesvos, a Greek island in the middle of the Aegean Sea. Lesvos had its fifteen minutes of fame throughout 2016 as the destination of choice for asylum seekers crossing the Mediterranean Sea from the Middle East and North Africa; today, the Moria Detention Centre on Lesvos is home to over 7 000 people seeking asylum in Europe.

Part of my job here is to coordinate a team of volunteers, making their schedules, training them, etcetera. About half of my team is made up of refugees, mostly young men between eighteen and twenty-five who live in Moria. They are translators, carpenters, cooks and general volunteers; their English skills vary wildly.

One of our translators is an eighteen year-old boy from Afghanistan who left his family at sixteen. About two weeks after my arrival in Lesvos, he found out I had taught English; after I showed him pictures of my students at BHSOH Learning Centre in Mae Sot, of their school and of Thailand, he asked if we could start English classes. Now, every Monday after work, I sit down with five of the volunteers and teach them English. This particular boy is a shining example to the rest: he’s bright, studies hard, and dreams of being a dentist.

Like my Mae Sot students, he speaks four languages (Pashto, Arabic, Farsi, and English). Like them, he fled his country, and like them, he is bright, inquisitive, and talented. He’s polite and soft-spoken and calls me ‘Miss Kat’. He constantly writes new English words in a battered notebook he keeps in his pocket. Unlike the kids at BHSOH and MSEP’s other partner schools in Mae Sot, he will not complete a high school education, because the Greek government has chosen to criminalize children escaping the violence of their home countries. No organizations are permitted inside Moria to provide educational services; no one may leave to attend Greek schools. My new young friend – remarkable, bright, and resilient, much like my smart BHSOH students – will likely never receive a high school diploma. He has been imprisoned here for one year, eight months, and nineteen days, as of February 23, 2018. He has had a deportation order for three months, meaning that he can be deported at any time.

Within all the Greek islands, only 10 refugee children attend Greek schools. The “lost generation” of Syria and Afghanistan has limited support for education; many do not even have access to basic necessities such as adequate shelter. Refugee and migrant children, whether in Greece or in Thailand, face unimaginable hardships, and access to education provides structure, safety, and security for children who otherwise have very little stability in their lives. Beyond that, it gives them hope for the future, for a life beyond forced migration! We can see the benefits very clearly in the Burmese migrant community of Mae Sot. Perhaps, someday, my only Afghan student will receive the education he deserves as well.

Kat in the classroom

Are you ready for Reverse Culture Shock? If you want to be a volunteer, be prepared!

By Loic Mercier, 2017 volunteer

This year upon my return from six months volunteering in Mae Sot, my annual family reunions have been exactly the same as every other year… except that I have felt completely different. Like every year, I have gone to parties on both sides of my family. Of course this year most of my relatives have greeted me with, “Hey! He’s back! So, does it feel good to be back?” I never know what to say.

I don’t want to start explaining that every morning I wake up surprised not to be hearing the call of a rooster or the strange squeal of a gecko that you never really get used to. There is not one day that I do not see myself biking down the highway on my single-speed bicycle with a basket full of worksheets still hot off the press for my students.

I cannot explain all that to my relatives. So I do the polite thing to do here in Canada; I talk about the weather. “It was quite a shock to walk through those airport doors in Montreal!” Then they’ll ask how hot it was in Thailand and I might try to describe it. Would they really understand that when we say, “It’s been a hot day,” it means that all we did was take turns under the cold showers before drying in front of the fan. I’m not saying that they are being inconsiderate,

but would anyone who hasn’t lived in Asia understand squat toilets? The absence of toilet paper? The idea that washing may be better than wiping? The fact that it has become a habit to wash my hands and feet many times a day? It’s just not something that is easily put into words… though I try.

I’m not trying to make my relatives feel guilty for not understanding the reality I have just experienced. Some go further and genuinely want to know: “So being a teacher: was it really different over there?” And a wave of nostalgia-infused memories comes over me as I am thrown back into my classroom where my students stand and call a collective, “Good afternoon teacher! Thank-you teacher! See you tomorrowww”, really dragging out that last syllable. Memories of shared lunches, squatting in a circle. When I say ‘shared’, I really do mean ‘shared’. Everything is shared and distributed in a fair manner. The students are fast eaters, and even faster digesters. My plate is not even finished, and my students have their cleats out and are ready to go play football… I don’t really want to go into all that. I am afraid of becoming too emotional. “So being a teacher: was it really different over there?”

I usually give a much more trivial response: “Sure, it was different, we had a bird in the classroom once…” And my uncle or cousin will answer, “Wow, a bird really?!” If I want to impress them I’ll say, “And we had one hell of a gecko living in in the basement! The thing looked like Godzilla!” and we’ll have a good laugh about it.

Rarely do I discuss the sharing som tum (spicy papaya salad) with other teachers, friends, or expats on a wooden plank floor. Rarely do I discuss all the evenings on the porch with my co-workers, friends, roommates… (Shall I use the words brothers and sisters?).

Then comes the big question, “Do you miss it?” I do miss it. I miss the different smells coming from the markets, whiffs of aromas you don’t quite recognise, the sound of the monks and their bells as they wander the street with their alms bowls when the sun is barely rising. I miss the greetings of those students. “Do you miss it enough to go back?” Of course some of them are inferring by that that having lived six months with Godzilla as a tenant and sleeping on two-inch mats, I must be happy to have come back to my orthopaedic mattress. I usually answer something along the lines of, “Sure, that would be the ultimate goal.” In fact I should answer. “Yes. That is all I want in the world.”

My mom jokes that I’m a spy leading a double life, one on each side of the globe. Of all my family members, I’d argue she’s the one who got it the closest.

Loic with his students in Mae Sot

Project Developments in 2017

Perhaps the most exciting undertaking of 2017 for our project was the videotaped interviewing of all of our partners in addition to some former migrant students who are currently teaching in migrant schools. This project, initiated and carried out by Emily Prangley Desormeaux (a former volunteer and project committee member), is still being completed as the interviews require both compiling and editing. We hope to have a “trailer” ready for our Thai-Burmese dinner and eventually to be able to post the interviews on our web site. The key learning from them was a clear message that even when our funds run short (since in the grand scheme of things our annual financial contributions are modest), our partners value the presence of young volunteers. In addition to the language learning their students experience, they are keenly aware of the value of cross cultural exchanges for their youth. Over time, as many organizations depart to attend to other world crises, they value our constancy and our recognition that international assistance remains critical for migrant youth who are always at risk of trafficking, child labour and the oppression of poverty and for whom return to Myanmar remains fraught.

At home, MSEP took a leap last year and launched its first golf tournament. Although relatively small as such events go, it netted an important $4000. Will we repeat it? We would enjoy hearing your thoughts as to whether or not we should. The tournament was a learning experience for us that we are still processing as we try to determine the most effective ways to reach out to our community for support.

Finally, we continue to seek more effective ways of engaging the Bishop’s and Champlain communities in terms of recruitment of volunteers and of faculty members to become involved in carrying the project forward. We have received a clear message that we are still wanted in Mae Sot. However, as the composition of our project committee evolves, we still face the challenge of how to make the project sustainable so that we can respond to our partners’ needs and provide youth from our campus with what is clearly a life-transforming experience. If you are interested in getting involved, please contact us!

Our Finances in 2017

Below is some information regarding our finances in 2017. The pie chart for revenues indicates that the Pathy Family Foundation donation received in 2016 provided $15,000 of our revenue for 2017. This coming year (2018-19) marks the third and final year in which that funding will be available to us. Thus we anticipate a drop in revenue. Funds raised by the project’s activities, charitable donations and donations from community organizations as well as other grants made up the remainder of our revenue. The expenditures chart here shows how we used our funds in 2017. $11,546 was given to our six partner schools as MSEP’s annual donation. In addition, some generous donations enabled us to make targeted contributions amounting to $25,000 to two schools with special needs. Volunteer support accounted for $17,666 of our expenses. In 2017, we also used some of our funds to support an internship and visit to partner schools in Mae Sot by one of our Project Committee members. As you can see from the chart, we spend very little on ourselves – because we are all volunteers! If you have any questions or would like further information about our project finances, please contact us. We are proud of our management and happy to respond.

See the complete details and charts on our Donation page.

Donors and Supporters 2017

We wish to thank everyone who has helped to make our project a success. Donations take many forms. Financial donations, donations of time and energy, raffle prizes, golf tournament sponsorships, in-kind donations of all sorts have all been deeply appreciated. In addition to those people and organizations noted below are many others who have faithfully supported our fundraisers. Thank you all!

We wish to thank these organizations & businesses:The Pathy Family Foundation |

And these individuals:Steve & Barbara Allatt |

Who we are and what we do

The Mae Sot Education Project (MSEP) is a community project based on the campus of Bishop’s University and Champlain College – Lennoxville in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Since 2004, we have provided assistance to six schools (officially called migrant learning centres or MLCs) for migrant and refugee youth from Burma/Myanmar whose access to education depends on support from the international community. In recent years we have also worked with other MLCs. Each year we select a group of young people from our campus to go to Mae Sot for six months. While there, they provide practical assistance to teachers and enrichment activities for children in the schools. They learn about the situation of displacement experienced by the Burmese people in Thailand as well as about the challenges for the Thai community in coping with a large population of refugees and migrants. Finally, they share their experience with Canadians. Over the last 14 years, MSEP has delivered over $126,000 in funding assistance (excluding two substantial grants given through specific donations) and as of June 2017, will have sent 56 volunteers to assist the migrant education community in Mae Sot.

The Project Committee is made up of members of the community, faculty from Bishop’s and Champlain, and former youth volunteers with the project. Currently, members are: Felix Duplessis Marcotte (2016 volunteer), Judy Keenan, Laurence Michaud (2015 volunteer), Graham Moodie, Mary Purkey, Garry Retzleff, Barbara Rowell (2005 volunteer) and Calila Tardif (2016 volunteer).

Contributions to the project are always welcome and tax receipts are issued. To make a donation electronically, go to our Donate Now page and follow instructions for donating through the Bishop’s University Foundation online or by cheque.

Recent Comments