Spring Fundraising & COVID-19: The MSEP Project Committee regretfully announces that it has had to cancel its annual Thai-Burmese Dinner, scheduled for April 18th, due to the current health crisis. See the News and Events section of our home page for more details.

MSEP in Transition – Innovating and Looking to the Future

New options for volunteers

MSEP is now 16 years old and it is time for some new thinking and planning. First, we wish to announce that in the year ahead, we will undertake a new initiative in order to better respond to the aspirations and needs of students on our campus. Along with offering and continuing to encourage a 6-month volunteer opportunity (June – December), we have decided to offer a 3-month volunteer option (which could be either June through August or September through November). This initiative is a response to the dilemma of students who would like to participate but who have undertaken challenging and restrictive programs that make 6-month commitments difficult.

At the same time, it has become clear that project sustainability will require financial investment. In the past, the project has fully-funded volunteers at a cost of approximately $4800 per volunteer. However, recognizing both the difficulty of raising funds and the value of the project to the volunteers, beginning in the coming year, both volunteer options will entail a modest financial contribution to the project from the volunteer in order to ensure its viability. Details will be announced in the coming months.

Both options will also include:

- The same preparation and support by the MSEP Project Committee.

- The opportunity to volunteer with Burmese community-based education and human rights organizations in Mae Sot, particularly for students who have more interest in international NGO work and less interest in classroom volunteering.

- For Bishop’s students: the opportunity to use MSEP volunteering to meet requirements of a 6 credit Global Studies Internship or alternatively an Experiential Learning complementary internship course.

- A commitment by volunteers to work together with the project committee to raise funds to enable MSEP to continue to support both volunteers and partner schools.

Finally, MSEP would like to encourage Champlain and Bishop’s faculty as well as retired teachers in our community to reach out to us regarding opportunities to engage in short-term teacher training or teaching stints in Mae Sot or alternatively, in academic research related to forced migration and education issues. A number of “post-ten” migrant learning centres and Burmese organizations in Mae Sot could benefit from volunteer teachers with teacher-training, language and computer skills. Research opportunities also exist for those interested in studies related to education of marginalized youth along with related issues such as child labour and trafficking, health and medical care or even conflict resolution in situations of displacement, etc. Teachers looking for professional development or retired teachers looking for new experiences might find the Mae Sot community quite stimulating and enriching.

Expenses for such experiences are relatively modest: travel, vaccinations might come to $1500 while on-site living expenses can easily be kept to $500 a month (depending on one’s needs and preferences). While MSEP cannot fund such activities, we are eager to facilitate them by providing information and assistance in making contacts, thus deepening the ties between our own community and our partners in Thailand.

In offering some of these options to students and past and present teachers, our key objectives remain, as always, to assist the migrant education community in Mae Sot and to help Canadians better understand the plight of people, particularly youth, displaced by repression and conflict. We hope that the opportunities described here will enable us to continue to work toward these goals.

Representing MSEP in Mae Sot in 2020: Bishop’s student Claire Keddy

In applying to volunteer with MSEP, Claire Keddy said: “This project combines my deepest passions in a unique opportunity to both teach and learn. My career goals include teaching English abroad and/or humanitarian aid work. I am passionate about immersive travel, cross-cultural exchange, education, and community development.” A third year Bishop’s University student who is pursuing a BA in Sociology & International Studies, Claire hails from Nova Scotia, but has gone out of her way to experience the world.

In applying to volunteer with MSEP, Claire Keddy said: “This project combines my deepest passions in a unique opportunity to both teach and learn. My career goals include teaching English abroad and/or humanitarian aid work. I am passionate about immersive travel, cross-cultural exchange, education, and community development.” A third year Bishop’s University student who is pursuing a BA in Sociology & International Studies, Claire hails from Nova Scotia, but has gone out of her way to experience the world.

During a “gap year” before coming to Bishop’s, she spent several months an Indigenous family in the Andean Mountains, participated in conservation and reforestation efforts in the Amazon Rainforest, and worked at an animal rehabilitation centre in Cusco. She also taught English to children of the Karen Hill Tribe in Thailand, as well as volunteering at an orphanage for six weeks before spending several weeks in Nepal teaching Buddhist monks-in-training. Since her return, Claire has started her own small volunteer project which aims to introduce youth to volunteer experiences abroad. Clearly, Claire is serous about international volunteering.

Volunteering and community development, eco-friendly living, healthy living and various forms of movement are among the values dear to Claire’s heart. When not busy with her studies or being immersed (through travel) in different cultures, she writes for her personal blog and enjoys yoga, pilates, strength training, hiking, baking, spending time in nature and being with family/friends. We at MSEP are thrilled to have her representing our project in Mae Sot this year as we begin a period of transition and experimentation with some new volunteer options. During the coming months, we will be carving out a role that will be enriching for her and at the same time help us sustain our partnerships in Mae Sot.

Volunteer Experiences

The people we meet in Mae Sot – Teachers and Students

By Mari Ann Burrows, 2019 Volunteer

I had the fortunate opportunity of volunteering at Parami Migrant Learning Center for MESP last year where I met some amazing people. The teachers at Parami are extremely dedicated to their students. Here are two examples.

Newman, the Grade 9 teacher, has been at the school since 2011. He teaches in Mae Sot during the week but has a house and family to which he returns each day across the border in Myanmar. When he first started teaching at Parami, he rode a bike from the border (a 40 minute to an hour ride) to the school each day. He would spend approximately 1000 baht ($42) a month to take a boat across the river every day to go teach at Parami. Now he has a work permit and a motorbike that he leaves on the Mae Sot side of the border for getting to school. A second teacher I met is Novemlin, who also grew up in Myanmar and has a Master’s Degree in Physics. She could teach in Myanmar but has stayed in Mae Sot because she fell in love with the community and the students and knows how great the need for qualified teachers is.

Novemlin and Newman

Everyone who goes to Mae Sot inevitably falls in love with the students and that is why the teachers stay even though they are paid very little (on average about $170 a month). The teachers at Parami go further to make the student’s life at the Migrant Learning Center an enjoyable learning experience. They not only work five days a week, plus go to conferences, plus hold meetings on how to better treat the students but also prepare activities for the students to enjoy on the weekends.

Being in Mae Sot was a wonderful experience for me because it really gave me a new perspective on life and how grateful I should be that I was raised in a place with free access to education. I always complained about having to go to school as a young kid, but now, experiencing how hard teachers actually have to work to make fun and interesting lesson plans and how their work day is not over even when their 8 hours is up, I have a new found respect for all my teachers.

Meeting promising young Burmese students is one of the real pleasures of volunteering in migrant learning centres. Here Mari Ann Burrows remembers one of these bright lights.

Eh Paw Klein with Mari Ann

Eh Paw Klein, one of my students at Parami Migrant Learning Center, is a gifted young girl who is extremely promising when it comes to learning English. She is excited and eager to learn from a native English speaker. While I was in Mae Sot, she spent most of her lunch hours with me in the sewing room practicing her English, telling me about her family and asking me about mine.

Eh Paw Klein had just transferred to Parami from CDTC School in Mae Sot. She lives with her aunt because her mother, father and little brother are back in her village in Myanmar. Her parents couldn’t afford to support her and send her and her brother to school so they sent her to live with her aunt. When her aunt-moved for work, she followed. She strives to learn English so that she can go to a good university and become a doctor or nurse. She said that if she achieves her goals, she wants to “help the poor people and their babies”.

Meeting Eh Paw Klein was truly a great opportunity for me. By talking with me over my lunches, she made me feel much more welcomed at the school. Our sharing of words in English and Burmese was fascinating, and I now know how to say simple words like apple, rice and fish in Burmese. I feel like meeting Eh Paw Klein not only impacted my life but hopefully hers too. To see such a young girl be so positive about being away from her family was very eye-opening to me. To be so mature at such a young age (13 years), to understand what her parents are going through and to come from a family with so little money and yet have the desire to give your money away to people less fortunate than you once you have money, is just incredible. Most adults I know are not as selfless and kind as Eh Paw Klein. Most of my friends at her age complained about not getting an allowance or being allowed to stay up past 10pm, but Eh Paw comes home from school every day and helps her aunt prepare supper. I am honoured to have gotten to meet such a great young lady, but I also feel bad for her that she is having to grow up so fast.

A Volunteer Challenge: Dealing with Conflicting Approaches to Misbehavior

By Anne-Constance Blanchette, 2019 Volunteer

In Myanmar culture, elder respect is incredibly important and children must obey orders at all times. The slightest disrespect or disobedience is unacceptable and for some teachers believe that the most effective response is through corporal punishment. While I had been warned and expected punishment methods, I was surprised by the frequency of the use of corporal punishment when I encountered it. I found myself asking: How can I bring this up? How can I help these children?

Migrant schools, through the help of organizations such as BMWEC, have been implementing strong child rights guidelines for teachers to follow. At the start of each academic year, teachers sign a contract agreeing not to use corporal punishment, to reduce such potential situations. However, corporal punishment does happen, and in schools where it is more routine, it was hard for me to deal with the overly harsh punishments. Children are sometimes hit with sticks and sometimes shamed in front of the other children. Yet migrant education leaders believe strongly that this is something that can change. There are child protection organizations in Mae Sot such as the Committee for Protection and Promotion of Child Rights (CPPCR). They try hard to educate teachers about alternative methods of classroom management and implement the rules against corporal punishment that do exist. However, they come up against some very traditional attitudes.

In our own society, when a child misbehaves often, people are quick to hypothesize that s/he has an attention deficit or hyperactive disorders and put him/her on medication. However, these resources are not available in all parts of the world, and are they even the best option as an alternative to corporal punishment? This to say that all around the world we all have similar issues, yet deal with them differently based on the resources we have. Everywhere, most school teachers work to help these children and to find solutions to help them live a childhood they deserve: without torment. In Canada our community revolves around children because they are the future; we also know that what they see is what they’ve learned and what will be replicated.

What can I do now with the knowledge that I have gained? To my surprise, the past couple of months since my return from my 6 months abroad have been some of the hardest months of my life. I am still trying to figure out what I can do to help children in these situations. I am trying to understand why I am embarrassed to be here studying rather than helping where there is a need. I understand that these issues will not be resolved overnight and may take generations to be solved and that perhaps there are even greater issues that must be solved prior. However, I do know that this experience will stay with me and push me to achieve the goals I strive for.

Migrants or Refugees? Who are our Partners?

A Reflection by Mary Purkey, Project Coordinator

Who is it that MSEP works with in Mae Sot? Are these people refugees or migrants? In recent times, these terms have become confused. Now, with changing climate and border security constantly in the news, we find ourselves questioning who needs protection and assistance. What about climate refugees? What does it mean to be an irregular (or is it illegal?) migrant? Nowhere are the terms as confusing as they are on the border between Myanmar and Thailand.

The problem is that the terms – like the situations of the people they describe – genuinely blur. The UN Convention definition of a refugee is someone who is fleeing persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, who is outside his/her country and has a well-founded fear of returning. It is a definition that many consider to be too restrictive as it includes neither gender nor generalized violence (two of the biggest sources of human misery today) as grounds for flight. Historically, the term “migrant” has referred to people who move to seek economic betterment. The reality today is that in many situations in the world, the people we call migrants are in fact fleeing conditions that we might also consider forms of oppression or even “persecution” even if they do not match the UN definition.

The problem is that the terms – like the situations of the people they describe – genuinely blur. The UN Convention definition of a refugee is someone who is fleeing persecution based on race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, who is outside his/her country and has a well-founded fear of returning. It is a definition that many consider to be too restrictive as it includes neither gender nor generalized violence (two of the biggest sources of human misery today) as grounds for flight. Historically, the term “migrant” has referred to people who move to seek economic betterment. The reality today is that in many situations in the world, the people we call migrants are in fact fleeing conditions that we might also consider forms of oppression or even “persecution” even if they do not match the UN definition.

For example, is it economic hardship or persecution when the presence of soldiers in a person’s village requires her to “donate” a significant portion of her rice harvest (even in a bad year) to the point where the rice farmer cannot feed her family? Is it economic hardship, oppression or actual persecution when farmland that has been confiscated during armed conflict is not then later returned to the farmers? Can government-induced economic hardship be considered a form of persecution? What about when a government fails to make health care or education available to people living in remote areas? If people in such situations remain outside their home country to seek a place where they can feed their families and live with dignity, are they migrants or refugees? A recent analysis of migration uses the term “survival migration” to refer to “people who leave their countries because they simply cannot secure the minimum conditions of human dignity in their country of origin” (Betts & Collier, Refuge, p. 44). Should “survival migrants” be entitled to the same protection as refugees as defined by the UN Convention?

How might this analysis apply to people from Myanmar/Burma in Thailand? Thailand has not ratified the 1951 UN Refugee Convention; Thai official policy grants refugee status only to a relatively small number of Karen people who fled Burma over the last two decades during which they were victims of a brutal civil war, the residual effects of which persist today. These people must stay in one of the nine refugee camps that dot the border in order to keep their status and the protection and material assistance that go with it. Just to be clear, this material assistance comes not from the Thai government but from a consortium of aid groups and governments called the Border Consortium (see https://www.theborderconsortium.org). Today, in part because of changing conditions in Myanmar and in part because the aid provided by the Consortium is steadily diminishing, the number of people in these camps has shrunk somewhat to around 100,000.

Along with these people are another 2 million or so people from Myanmar who live outside camps and thus are not legally entitled to be called refugees or to receive protection. They are supposed to have work permits to be legal and avoid deportation, though many cannot pay for the permits and have no documentation. What is the difference between these people and those in the camps? They are a more mixed group, but apart from the fact that they come from a wider variety of ethnic, linguistic and religious groups, they are not so different from the Karen refugees living in the camps. In many ways, they match Betts’ and Collier’s definition of survival migrants. In some cases, they are people who used to live in the camps but who could not stand the inactivity and isolation in these places and so chose to become “illegal”.

For both groups, the situation in their home country has evolved but still fails in fundamental ways to provide the minimal level of security and well-being to which humans are entitled.

Finally, do “survival migrants” deserve assistance and protection? Surely, our shared humanity calls upon us all to work to create conditions of life that enable humans to live in dignity wherever they are. The terms used to describe these people are indeed important in international law, or at least they have important consequences when deciding who might be entitled to asylum or permanent resettlement. However, when considering support for communities of people trying to carve out a dignified place for themselves in a world fraught by hard (and ultimately arbitrary) borders, constant instability, both political and social, and now changing climate, the question is really not whether but how. The challenge to MSEP working with the migrant education community in Thailand is how to use our small capacity to contribute to an answer to that question effectively.

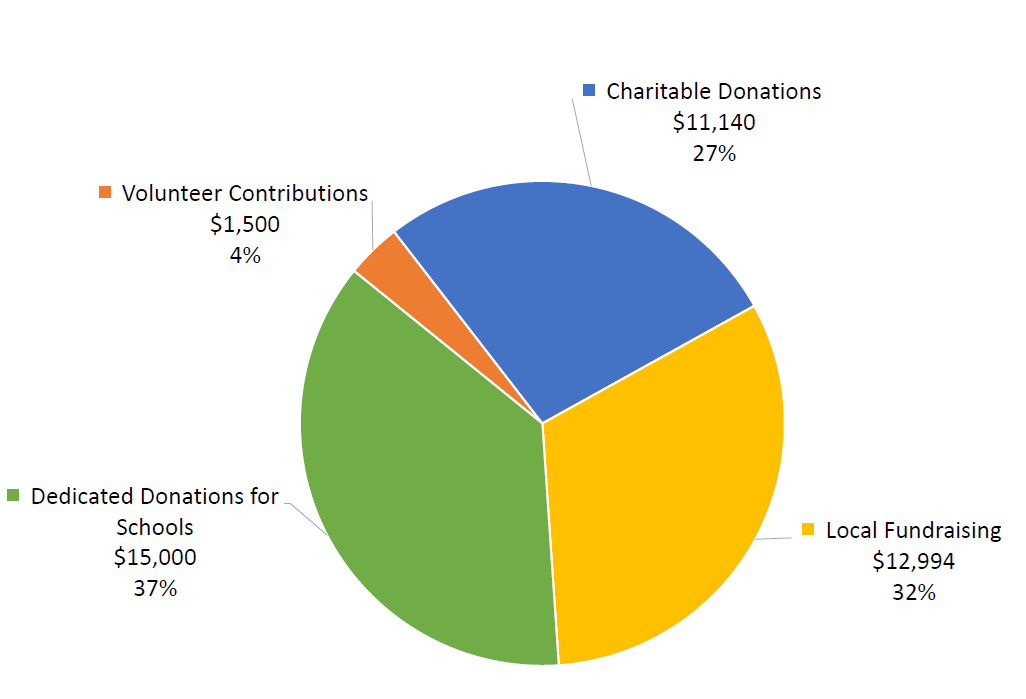

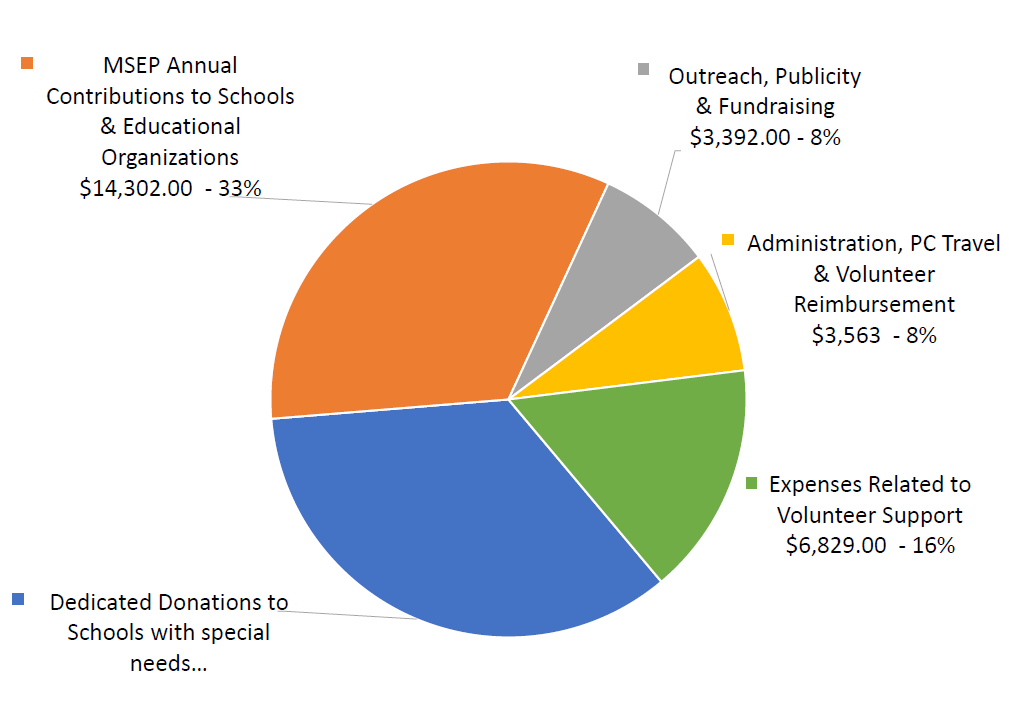

Financial Situation in 2022

As the pie charts below indicate, in 2022 MSEP received wonderful support from our donor community and thus were able to make significant contributions to partner schools in Mae Sot. What the charts do not really show is that our capacity to send volunteers to Thailand for extended periods has been deeply affected by events of the last years. While prior to COVID we had teams of 3-5 students going to Mae Sot, in 2022, we supported only one volunteer in Thailand and then for only three months with a cost almost as high as sending several volunteers in past years. Flights to and accommodation in Thailand have become more expensive, making it difficult to estimate costs going into the coming year. It will take another year for us to assess the impact of the changes. However, knowing how important our presence is to our partners, we are actively seeking ways to meet the challenges.

Revenue, 2022

Expenditures, 2022

Donors and Supporters from January 2019 through January 2020

We wish to thank everyone who has helped to make our project a success. Donations take many forms. Financial donations, donations of time and energy, raffle prizes, sponsorships, in-kind donations of all sorts have all been deeply appreciated. In addition to those people and organizations noted below are many others who have faithfully supported our fundraisers. Thank you all!

We wish to thank these:

Organizations & Institutions:

Bishop’s University

Champlain College – Lennoxville

Oasis Christian Centre

Pathy Family Foundation

SECCL (Champlain Teachers Union)

St Mark’s Chapel

University Singers

Businesses:

Boulangerie Les Vraies Richesses

Chanchai Restauraant

Clarke & fils Ltee

Familiprix (Lennoxville)

Follett’s Bookstore

Global Excel Management

Golden Lion Pub & Brewery

Importation Batavia

J. L. Lebaron Ltee.

La Boutique Joséphine

Maison de Cinema

Businesses:

Manoir Hovey

Provigo (Lennoxville)

Racine Santé

Restaurant Folle Thérière

Restaurant Rima

Restaurant Shalimar

Saveurs & Gourmandises

Siboire Microbrasserie

Thérapie Beauté

Trulere Bachand

Visite sous Terre Capelton Mines

Individuals:

Kathleen Adams

Karen Allatt

Steve & Barbara Allatt

Loic Arguin-Mercier

Catherine Beauchamp

Pamela Bertram

Carinne Bevan

Susan Black

Stephen & Helen Black

Colleen Bobbitt

Heather Bowman

James & Helena Brodie

Caroline Chabot Chartier

Claude Charron

David Chodat & Daniella Berenstein

Janet Cowen Weber

Norman Currier Estate

Gerald Cutting

Melanie Cutting

Lucinda Doheny

Dinah Duffield & Tim Doherty

David Dutton

Adele M. Ernstrom

Lewis & Cathy Evans

Frances Fisher

Jennifer Garfat

Tyler Gordon

Derek Heatherington & Jessica Gagnon

Meryle & Roger Heatherington

(Additional donation by Meryle Heatherington in loving memory of Joyce Standish)

Individuals:

Randi Heatherington

Joanne Hebert McLeod

Kristyne Houbraken

Lin Jensen

Murray Johnston

Peter & Carolyn Jones

Veronica Kaczmarowski

Jackie Keeley

Judy Keenan

Nelly Khouzam & Andrew Bass

Nancy & Ralph Knudson

Brian Kyle

Julien Lacombe

J. L. LeBaron

Naisi LeBaron

Real & Suzanne Leclerc

Joanne Marosi

Tom & Barbara Matthews

Pam & Stuart McKelvie

Sheila McLean & Brian Talbot

Fiona McLeod & Michael Goldbloom

Lissa McRae & Bill Robson

Isabelle Menard

Libby Mills

Meaghan Moniz

Dugal Monk

Queenie & Carlton Monk

Graham Moodie

Michael & Carol Mooney

Brandin Moores

Individuals:

John R. Oldland

Kathleen Olson

Angie & Denis Petitclerc

Emily Prangley Desormeaux

Peter Provencher

Mary & Robert Purkey

Susan Renaud

Garry & Marjorie Retzleff

Mary Rhodes

Nancy Robert

Allan Rowell & Nancy Baldwin

Barbara Rowell

Martyn Sadler

Gill Seale

Cindy Smith Tryor

Clarissa Smith

Stephen & Kathy Stafford

Mary Sweeny & Jean-Marc Francius

Beverly Tabor Smith

Richard Thompson

Heather Thomson & James Sweeny

Nisha Toomey

Miles Turnbull

David Turner & Carole Martignacco

Sandra Ward

Alexei Warwick

David Webster

Harvey White

Donating through the Bishop’s Foundation

If you wish to donate to MSEP through Bishop’s University, the Donate Now button will take you to the Bishop’s University Foundation’s site for making donations. Once on the donation page, for the designation, choose “other” from the list of options and then manually type in “Mae Sot”. You can then complete the rest of the form. Your donation to MSEP will be processed through the Bishop’s Foundation. You will automatically receive an e-receipt, and the Foundation will send a thank you card in the mail.

Alternatively, you can donate by cheque through either the Bishop’s Foundation or the Champlain College Foundation at our project address: Box 67, Champlain College – Lennoxville, 2580 College St, Sherbrooke, QC J1M 2K3. Be sure to include the name of the Foundation and MSEP on your cheque.

Thank you very much for your support.

Who we are and what we do

The Mae Sot Education Project (MSEP) is a community project based on the campus of Bishop’s University and Champlain College – Lennoxville in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Since 2004, we have provided assistance to six schools for migrant and refugee youth from Burma/Myanmar whose access to education depends on support from the international community. In recent years we have also worked with other schools. Each year we select a group of young people from our campus to go to Mae Sot for six months. While there, they provide practical assistance to teachers and enrichment activities for children in the schools. They learn about the situation of displacement experienced by the Burmese people in Thailand as well as about the challenges for the Thai community in coping with a large population of refugees and migrants. Finally, they share their experience with Canadians. Over the last 16 years, MSEP has delivered over $161,000 in funding assistance (excluding two substantial grants given through specific donations) and as of June 2019, has sent 64 volunteers to assist the migrant education community in Mae Sot.

The Project Committee is made up of members of the community, former faculty from Bishop’s and Champlain, and former youth volunteers with the project. Currently, members are: Felix Duplessis-Marcotte (2016 volunteer), Tyler Gordon (2018 volunteer), Judy Keenan, Graham Moodie, Dania Paradis-Bouffard (2017 volunteer), Mary Purkey, Garry Retzleff, Barbara Rowell (2005 volunteer) and Calila Tardif (2016 volunteer).

Recent Comments